Op-Ed: What Are We Designing For?

- Matthew Messere

- Mar 8, 2021

- 3 min read

Much more goes into the design of our built environment than one may think.

March 8, 2021 at 11 am EDT

Written by Matthew Messere

The typical style for an architecture studio is to find a problem then suggest a narrated solution. What follows is a series of analyses that observe site conditions that promote an informed story. That story then becomes the architecture.

During the process, an important question is often asked: who are we designing for? As it seems obvious, we as architects are mostly designing for people. However, this becomes much more convoluted once you dive deeper into an architecture studio. The question oftentimes transforms into “what are you designing for?” This is so much to the point that in the early phase of the Covid-19 pandemic, the architect became a go-to source for op-eds regarding the future of our built environment. The truth is, however, architects are not oracles despite our knack for speculation and the imagination.

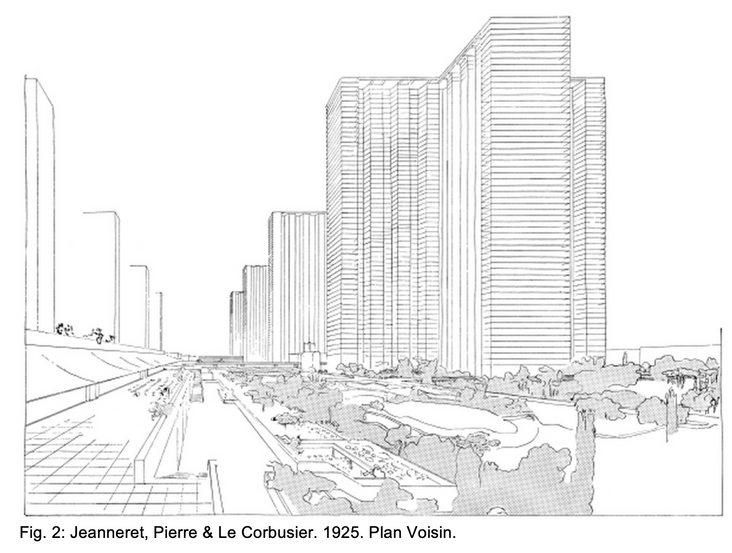

In its skeletal form, architecture has been a field fascinated with representation. Architects like Étienne-Louis Boullée materialized the imagination through speculative drawing (fig. 1), while Le Corbusier envisioned a city for the modern epoch, addressing the problems that plagued old cities (fig. 2). Architects have long created ideas for utopian (or dystopian) life. In particular, the period after World War II reveals a telling story similar to our current predicament—a time of great restructuring, a new normal. What are we designing for? What way of life do we imagine for ourselves, for our world?

To post-war Britons, the likes of Alison and Peter Smithson, Reyner Banham, and the groups of Archigram and others, the world was rapidly changing. Their reactions formed from the major shift in how architecture was produced. America had grown its global influence as a paternal figure to a ravaged western Europe, and the field of architecture was changing under its influence. The role of the architect was uncertain as the construction industry revolutionized itself around an economy of standardization. Rather than designing a building from the ground up, architects began to assemble prefabricated pieces to create space.

As a critique, speculative architecture of plug-in cities perpetuated the idea of prefabrication to the extreme (fig. 3), and the new brutalist movement responded by emphasizing assembly and references to individualization (a precursor to American brutalism or Concrete Modernism). We see these as near opposite reactions to the sociopolitical climate of the 1960s. On one hand, architects imagine architecture as a self-assembling system that can be adapted over time. On the other, American brutalism provided a solid permanence and the imageability as immortal, forever unchanged.

What we see is that neither of these movement’s theories of the future of architecture and the built environment were correct. Plug-in cities like Kisho Kurakowa’s Nakagin Capsule Tower (fig. 4) have not seen the changing or adding of its capsules. Similarly, many brutalist buildings have been received negatively by the public and thus have been neglected or even demolished (fig 5). One could say that these buildings have become obsolete. The buildings of the 1960’s are now reaching the end of their lifespans as new technologies and uses are developed. This leads us back to the all-encompassing question: what are we designing for?

While we must consider time as an important factor to architecture and our built environment, it is multifaceted. It cannot simply be neglected or seen through the lens of utopic action that would only happen in a perfectly inhumane system. Similar to economics and government, design, policy, and action must be taken for our present disposition. Our actions must be targeted towards scales of temporality: those that exist in the current and near future, and those that are long-term. Design cannot be concrete; rather, it must have the ability to become reflexive to our environment, acknowledging its paradoxical temporality and immortality at the same time.

About the Author: Matthew is a fourth-year architecture student at the Wentworth Institute of Technology. His interest in design as a method to investigate culture began with a series of books on early twentieth century architecture theory, developing ideas on how theoretical understandings of our environment provide context to the culture in which a society sits in. Inspired by the readings, Matthew writes frequently on theory, conducts research on contemporary Qatari architecture with faculty from Wentworth and MIT, and has been an editor of the Wentworth Architecture Review since his sophomore year. When he is not busy reading history and contemporary theory, he enjoys swimming and exploring new museums.

Eloquently written, and beautifully put. I love that you are changing the common narrative that architects are oracles or "predictors" of the future, and repainting architects as inquisitive and imaginative people who must still remain flexible due to the unpredictability and paradoxical nature of the future. The truth remains that no one can predict the future, and that attempting to be too flexible or concrete has its respective downfall.

I just wonder about the conflict between self-assembling systems and American brutalism, and I question whether or not this is a false dichotomy. Though a well-established and well-defended conflict, there are dangers associated with every simplification–examining Kisho Kurakowa’s Nakagin Capsule Tower was a great example of a self-assembling, adaptive system and…